This guest blog features a summary of research by Allison Kelley, a graduate fellow studying preventive conservation at the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation. For her research, Conserv provided access to their analytic tools and wireless sensors. Banner image courtesy of the Golf Museum at James River Country Club

Rarely in the past eighteen months have plans been able to move forward in the way we anticipated. In the middle of my graduate education, I had to shift my expectations for what my projects would look like and what hands-on skills I would really be able to learn.

Fortunately, as a result of creative planning and the accessibility of remote environmental monitoring, the semester-long preventive conservation project that I had planned for the spring of 2021 was able to proceed with no major alterations.

I wanted a project that would offer a hands-on, real-world experience where I could learn on the job while still having the support of my supervisors and guest instructors. To achieve this, I conducted a preservation survey of a small collection in my hometown, the Golf Museum at the James River Country Club.

Fig. 1: An overall view of the Golf Museum housed within the James River Country Club

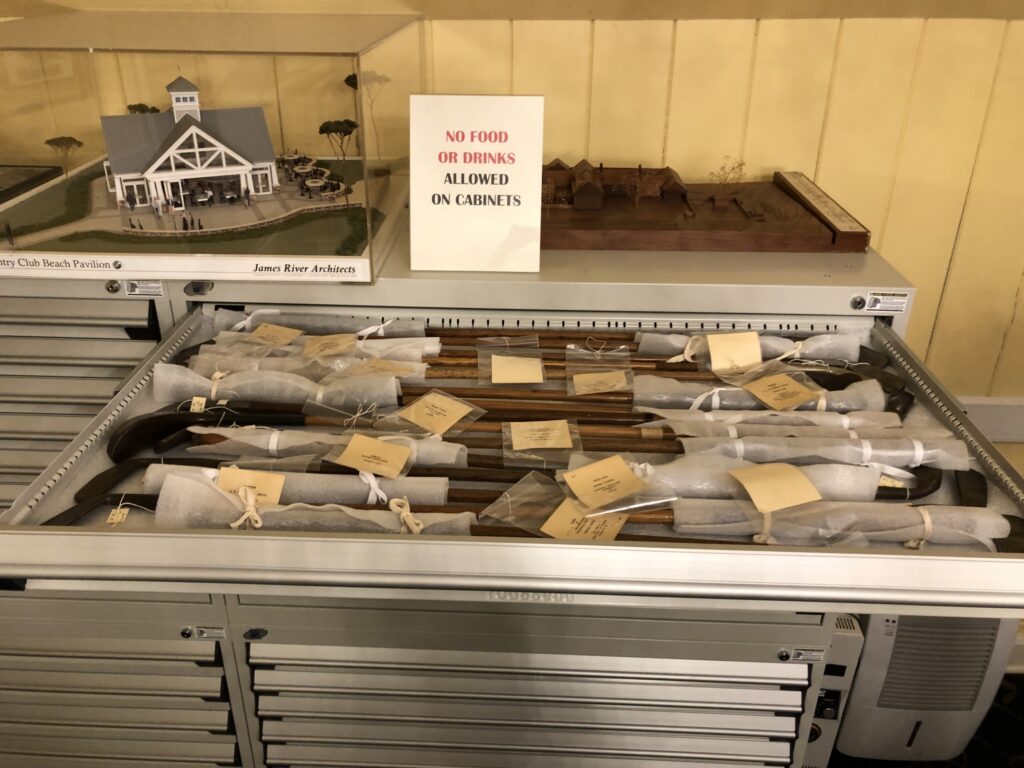

The Golf Museum was established in 1932, coinciding with the formation of the James River Country Club that houses the collection. Using its impressive holdings of early golf clubs, golf balls, and nearly 400 volumes on sport and golf, the museum focuses on telling the history of the game. The display area and storage space were updated ten years ago, and the museum’s board sought an opinion on what they could do to maintain good preservation standards going forward.

Fig. 2: This drawer holds examples of early golf clubs that were made with wooden shafts. There are 200 clubs in the collection.

Fig. 3: Boxes of golf balls of all different ages and makes. Note the very large “featheries” in the top right corner. The ball is formed of stitched leather that is stuffed with feathers!With a mixed material collection such as this one, providing a stable environment is one of the best ways to preserve the collection. Too much humidity could cause corrosion of the metal, too little humidity could cause the organic elements to stiffen and become brittle, and abrupt shifts in either direction could result in warping and cracking in the wooden components. As the name suggests, the James River Country Club is located on the banks of the James River in the southeast coastal region of Virginia, where high relative humidity and sporadic temperature fluctuations are typical weather features. For these reasons, understanding the environmental control system and assessing its efficacy was a major component of my survey.

Fig. 4: This is the display case where one of the wireless sensors was placed. It contains golf clubs and balls and has a history of moisture issues that have since been resolved. Placing one sensor here helped me understand the collection items’ microclimate and monitor for any undetected relative humidity problems.

Conserv generously shared a Starter Kit with the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation to facilitate research projects and student work. I took the kit home with me for winter break and was able to install the wireless sensors and gateway easily at the Golf Museum. I set one of the sensors in a display case on the main floor (pictured in Fig. 4); I was curious to see how conditions fluctuated in this unsealed case and what sort of buffering capacity the case had.

I placed the second sensor in one of the storage units on the second floor (pictured in Fig. 5). The room with the storage units is a multipurpose space that sees regular use. It houses board meetings and bridge club, and is sometimes used as a babysitting space while parents eat dinner downstairs. The multipurpose room also has numerous windows while the museum space does not. I was interested in observing the differences in the conditions between the second floor storage space and main floor exhibition space.

Fig. 5: Storage units that house golf clubs and balls, site of second sensor.

With the sensors online, I was able to remotely check climate conditions using the Conserv Cloud.

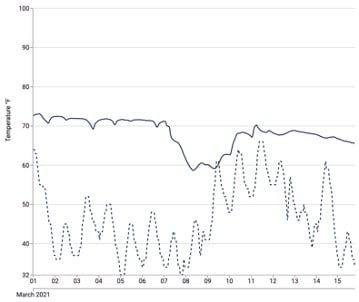

The numbers were largely steady, but there was a particular moment of excitement. On March 7th, the boiler broke and there was no heating capacity in the whole building for a two-day period in the middle of a cold snap. I saw this as an excellent test of the buffering capacity of the display case and storage unit.

With Conserv Cloud’s built-in analytics, I compared the local weather data to the temperature readings from the sensors. Happily, while the outside lows got down to 32 °F, the temperature only dropped to 60 °F in the display case and 63 °F in the storage unit, and the temperatures plateaued until the heating system was repaired.

This indicated to me that both spaces are well insulated and the building envelope has an excellent buffering capacity. The museum could be assured that if regular building and environmental systems are maintained, conditions are likely to remain stable and the collection is unlikely to experience sudden or drastic swings in temperatures.

Fig. 6: Graph of hourly temperature data collected from March 1 – 15, 2021. The solid blue line shows the data from the sensor in the museum display case and the dotted blue line shows the local outdoor temperatures.

Conveniently, I could observe the real-time data for this serendipitous “test” from my apartment in Wilmington, DE, 200+ miles away from the sensors.

Over the course of the semester, I had opportunities to consult with preservation professionals who specialize in analyzing environmental data. The ability to pull up the data and control the variables, comparisons, and intervals made for fruitful conversations where we could get to the heart of the relationships between temperature, relative humidity, and dew point and what they can reveal about the environmental control and stability of a space.

After a semester of collecting data, interviewing staff, and consulting with guest lecturers, I was able to put together a report for the Golf Museum highlighting strengths and areas for possible improvement that the museum can use to inform future preservation endeavors.

Without the Conserv Starter Kit, I would not have gotten the experience of working with and interpreting environmental data, a critical aspect of preventive conservation. The convenience of the interface and the ease of setting up the equipment meant I had one less thing to worry about in a very busy semester.

I want to say thank you to Conserv for their thoughtful, feedback-informed design and their generosity in sharing this technology with emerging professionals in the field of preservation.

For more information about the Golf Museum at the James River Country Club, you can visit their website at http://jamesrivergolfmuseum.com/

If you have any questions about environmental monitoring, integrated pest management, or just want to talk about preventative conservation, please reach out to us! Don’t forget to check out our blog or join our community of collections care professionals where you can discuss hot topics, connect with other conservators or even take a course to get familiar with the Conserv platform.